- Start with the equation of gravitational force:

\[

\boxed{F = G \frac{m_g M}{r^2}}

\]

Where:

- \(F\) is the gravitational attraction force,

- \(G\) is the gravitational constant,

- \(m_g\) is the gravitational mass of the falling body,

- \(M\) is the mass of the attracting body (e.g., Earth),

- \(r\) is the distance between the centers of mass of the bodies.

According to Newton’s Second Law, we have:

\[

\boxed{F = m_i a}

\]

Where:

- \(m_i\) is the inertial mass of the body,

- \(a\) is the acceleration produced by the force.

Equating the two expressions for \(F\):

\[

m_i a = G \frac{m_g M}{r^2}

\]

Isolating \(a\):

\[

a = G \frac{m_g}{m_i} \cdot \frac{M}{r^2}

\]

- Now, we assume as an experimental postulate the equality between gravitational and inertial mass:

\[

\boxed{m_g = m_i}

\]

Substituting:

\[

\boxed{a = G \frac{M}{r^2}}

\]

Important: This acceleration does not depend on the mass of the falling body.

This explains why a feather and a lead ball fall with the same acceleration in a vacuum, as demonstrated in the experiment on the Moon by the Apollo 15 mission.

This equality \(m_g = m_i\) was known since Newton, but was verified with high precision in the experiments of Eötvös and others. Later, Einstein elevated this equivalence to a fundamental principle of modern physics: the principle of equivalence, cornerstone of General Relativity.

- Equations of motion

Suppose we drop two bodies (the feather and the lead ball) from the same height \(h\), with initial velocity zero.

In vacuum, a freely falling body is subject only to the gravitational force, which makes its acceleration constant and equal to gravitational acceleration \(g\). In this context, the motion is uniformly accelerated, with constant acceleration \(a = g\) directed downward.

- Equation of uniformly accelerated rectilinear motion

According to classical kinematics, the position \(y(t)\) of a body in uniformly accelerated rectilinear motion is given by:

\[

\boxed{y(t) = y_0 + v_0 t + \frac{1}{2} a t^2}

\]

where:

- \(y_0\) is the initial position,

- \(v_0\) is the initial velocity,

- \(a\) is the constant acceleration,

- \(t\) is the time elapsed since the beginning of motion.

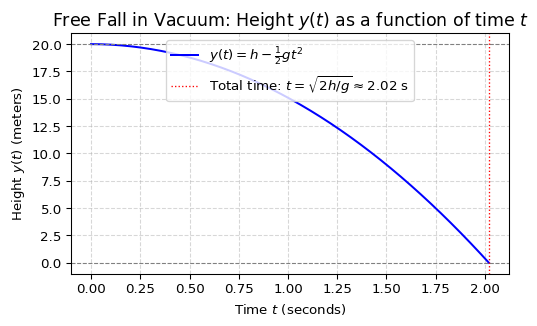

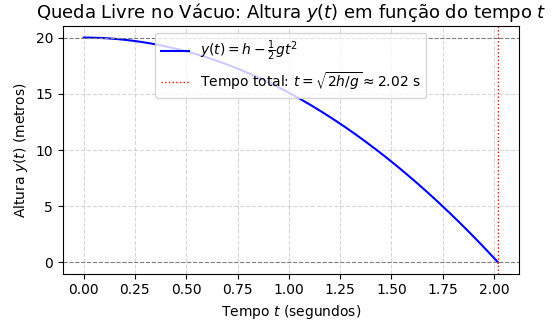

- Application to free fall

For a body dropped from rest:

- Initial position \(y_0 = h\),

- Initial velocity \(v_0 = 0\),

- Acceleration \(a = -g\), since the vertical axis is oriented upward and gravity acts downward.

Substituting into the position formula:

\[

y(t) = h + 0 \cdot t + \frac{1}{2} (-g) t^2 = h - \frac{1}{2} g t^2

\]

Thus, the equation describing the vertical position of the falling body at time \(t\) is:

\[

\boxed{

y(t) = h - \frac{1}{2} g t^2

}

\]

- Physical interpretation

- The term \(h\) represents the initial height from which the body was released.

- The term \(\frac{1}{2} g t^2\) represents how much the body has “descended” due to gravitational acceleration after time \(t\).

- The position \(y(t)\) decreases over time, until it reaches the ground (\(y = 0\)).

This equation clearly shows that displacement is proportional to the square of time, a typical feature of motion with constant acceleration.

- Considering \(y=0\) as the ground, the fall ends when \(y(t) = 0\):

\[

0 = h - \frac{1}{2} g t^2 \implies \frac{1}{2} g t^2 = h \implies t^2 = \frac{2h}{g}

\] \[

\implies t = \sqrt{\frac{2h}{g}}

\]

That is, the time for the object to reach the ground is:

\[

\boxed{t = \sqrt{\frac{2h}{g}}}

\]

Important: this time does not depend on the object’s mass.

Since the feather and the lead ball are subject to the same acceleration \(g\) and are released from the same height with zero initial velocity, the time to reach the ground is the same, given by:

\[

\boxed{

t_{\text{feather}} = t_{\text{ball}} = \sqrt{\frac{2h}{g}}

}

\]

Therefore, in vacuum, feather and lead ball reach the ground at the same time.

In media with atmosphere, such as on Earth, the feather falls more slowly due to air drag, which depends on the shape and density of the object. In vacuum, however, this effect disappears — and then the only factor that matters is the gravitational acceleration \(g\), which is the same for all bodies.